Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

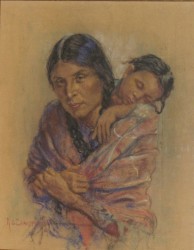

Two University of Lethbridge students are looking to capture the stories behind the portraits and drawings by artist Nicholas de Grandmaison.

Maria Livingston and Karissa Patton are reaching out to families and individuals across the province, people who knew the famous portraitist or whose family members were subjects of his work.

The memories and stories will add to the depth of meaning in the university’s considerable collection of de Grandmaison’s work.

Even the smallest stories will help, says Livingston, who is Cree, a hoop dancer and an artist.

“When I look at his paintings, I get lost in them,” she said, admitting she feels a personal connection to the portraits. “You just want to know the story, how he captured the faces, expressions and character. You can see their cultural pride.”

The Russian-born de Grandmaison came to Alberta by way of England in 1923, and spent the next 45 years travelling throughout the prairie regions of Canada and the U.S., capturing with poignant detail the faces and character of the First Nations people. Often, he spent time in their homes getting to know their ways of life. So popular was de Grandmaison among the people of southern Alberta that he was made an Honourary Chief of the Peigan Nation in 1978, the year he died.

After the artist passed away, the BMO Financial Group purchased 100 of his works from his family. In February, they donated 67 pieces from that portfolio to the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, which already owned a significant de Grandmaison collection. As part of that gift, BMO also gave $50,000 for research and preservation of the pieces.

In May and June, the donated portraits were presented in a public showing at the gallery. Josephine Mills, gallery director and curator, noted that the BMO donation inspired a search for ways to encourage new work from First Nations artists. As part of that effort, the Oral History Project was launched.

In order to collect the stories and follow protocol, Livingston and Patton worked with Roy Weasel Fat, vice-president of Academics at Red Crow College and now on secondment to the University of Lethbridge.

“I brought four of the Elders (from the Blood Reserve) ... to the gallery, and they were able to identify 19 of the people, and provide some information on them. They suggested that they could assist (the students) in connecting with the family members in our community,” said Weasel Fat.

The Elders had important knowledge to share, he says. “When they look at the picture, it’s more than just the likeness of the person. There’s a story in it. They could look at the braids and the shirts and if they had a particular red fabric tied in the braid, they know what these things mean.”

Weasel Fat recognized one of the paintings, which depicted Sorrow Horse. “He was the first person on our reserve who built a great big horse barn and planted trees all around. He was the first to buy a vehicle. There were quite a few who were very successful back around the 1920s.”

One of the earliest interviews had a family connection for Livingston, bringing it close to home. “My sister’s husband’s father was painted three times as a child, so that’s who we interviewed. He talked about how things were and some little stories. He said he (the artist) was really relaxed, just sitting there smoking his cigar and visiting.”

Livingston said they had also completed two additional interviews, one with a student’s great grandparent and the other with the daughter of the man who initiated de Grandmaison as an honourary member of the Peigan nation.

Recording an oral history like this is fitting, she says, given the traditions of story-telling as a way of passing history from one generation to the next in Native culture. “Everything was passed down orally, and this (project) reinforces that.”

Although Livingston was reluctant to share details from the interviews, she says they did talk about a thunder pipe ceremony. “I’ve been involved in some Blackfoot ceremonies, but I didn’t know anything about this one.”

As for the future of the de Grandmaison collection and the Oral History Project, Livingston said one of the goals is to hold an annual display at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery and invite students and community members to share the paintings and the stories.” Video clips of parts of the interviews from the oral project would also be included.

- 1866 views