Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

“It’s about time they showed the wonderful image-making and history of the Anishnabe people,” said artist Bonnie Devine about the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) and its exhibition, Before and After the Horizon.

“It’s part of the art history of Ontario. It makes me happy. But I also wonder, why did they take so long?”

The exhibition features Anishinaabe artists of the Great Lakes had its official opening on July 30 and was attended by about 300 people. It runs until November 25. Before and After the Horizon provides an expansive look into the artists’ values, beliefs and the political struggles against colonial invasion.

The work is organized thematically and explores six concepts of shared relevance to Anishinaabe people—place, cosmos, church, contested space, cottager colonialism and many worlds.

The show combines traditional art objects from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s with what is called contemporary art by artists like Norval Morrisseau, Robert Houle, Arthur Shilling and Carl Beam, among others.

The traditional art objects, such as the carved wooden bowl with thunderbirds or the floral beaded leggings and carved blackstone pipe, all have cards that read ‘maker unknown’.

The work is breathtaking in its beauty and its brilliance.

“There is so much content in this show,” said Devine, “spiritual content, historical content. There is anger, there’s passion, there’s a lot of truth. Some of it is historical objects and some of it is completely out there, intellectual engagement with politics and social issues. This is the role of the artist, to bring these things to life. A lot of the work says, I want to tell my story and I want to tell it so I can teach you.”

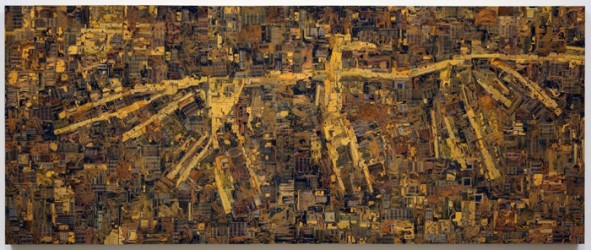

Saulteaux artist Wally Dion tells the story of the Thunderbird and its enduring presence in contemporary society. Dion’s imposing work titled Thunderbird was done in 2008 using computer scraps to create an image familiar to the Anishinaabe. It’s clever in its recycling of modern-day hi-tech refuse to tell the story of the Thunderbird, a being as ancient as the world itself. And in so doing, Dion tells the viewer that the Indigenous people of this land are alive and their values and beliefs are still relevant in contemporary society.

Anishinaabe artist Frank Shebageget created a large mobile of hundreds of model planes made of balsa. It’s titled Beavers and refers to the floatplane that has enabled colonial incursion into the most isolated territories of the Anishinaabe. The work evokes images that are haunting. Workers fly in to extract resources and destroy traditional hunting and trapping grounds. Children flown out to residential schools, away from their families, their communities and their culture.

Robert Houle is a Toronto-based Anishinaabe-Saulteaux artist and curator who has three pieces in the show. Parfleche for Norval Morrisseau is done in shades of blue with an abstract representation of the Thunderbird seeming to hover in the sky over the water. Houle knew Morrisseau since the 1970s and had a deep respect for his work and his spiritual strength.

Parfleches were often used as medicine bags by the Plains Indians and this painting is a fitting and celebratory homage to the late artist whose Anishinaabe name was Copper Thunderbird.

In an interview with Houle following the opening, he said he was pleased about the exhibition. But, “things have not changed very much in terms of how the larger society defines us,” he said.

“The colonial thinking is so ingrained. It’s such an integral part of their psyche for the simple reason that if you’re growing up white, you see things a certain way—the way the nation was built, the way the nation has built its national norms. Nobody, except for us, sees things differently. We have to point out our exclusion because they don’t even understand the exclusionary things that happen.”

Andrew Hunter, curator at the AGO, said one of the things the exhibition has brought is a realization that the institution has to be consistently engaged “with this complex and difficult dialogue about the colonizer and the colonized, between the newcomer and the established cultures. One of the great things about a show like this,” Hunter said, “is it challenges everyone whether you’re First Nation or not to think about the place of creative work in daily life…art is about solving issues or challenging ideas.”

- 1921 views