Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

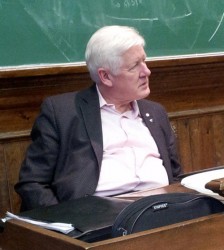

The history of Canada is based on a series of misunderstandings as well as understandings, Bob Rae told an audience of mostly law students at the University of Toronto on March 19.

Rae resigned last year from his position as Liberal MP for the Toronto Centre riding to take on the job of Advisor to the Matawa Chiefs Tribal Council regarding the development of an area in The Ring of Fire in northwestern Ontario.

Canada has two narratives, Rae said, the colonial or “Imperial story of Canada which is that Canada was discovered by Europeans, that Europeans fought over which country would rule and that whoever lived in Canada was subject to the law of the majority which reflected the narrative of the settlers.”

The other narrative is the Indigenous one. There were people living here who had customs, languages, beliefs and laws, and a relationship with the land that was very different from the Europeans.

“It is taking us a long time as a country to fully understand the racism and the profound bias…” upon which the Imperial view is based, said Rae. “What seems to me,” he continued, “is that we’re increasingly having to come to terms with these two ways of looking at the country and understanding that it requires some real reconciliation.”

Reconciliation has three phases, he said. The first is telling the truth, the racist origins of the policies and actions, and the implications for those on the receiving end.

The second phase is, “anger and indignation and frustration and people coming to terms with the truth on both sides,” Rae said. “People understanding we did this, these things were authorized…” he continued.

Then there’s reconciliation, figuring out how to go forward in ways that will make a difference. In Rae’s view, the process of reconciliation is just starting.

Two things make reconciliation such a pressing current issue in Canada, he said. “One is the demographic revolution which is taking place which is literally transforming the Aboriginal populations and its relationship to the rest of the country. There’s a 20 per cent increase in the Aboriginal population, according to Statistics Canada between 2006 and 2011, from 1.1 million to 1.5 million.” This is coupled with a steady increase in Aboriginal people moving to urban areas.

The second thing, said Rae, is that oil and gas exploration, and mining for gold and diamonds means development is encroaching further and further north, “…into areas that have traditionally been areas where First Nations people have lived and worked and felt to be their traditional territory.”

Aboriginal issues are no longer “out there”, he said, “they’re actually here in Toronto and they’re in every major urban centre, and society has to deal with it.” It’s brutal trying to get people’s attention, he said, “because the awareness is not there, the sensitivity is not there, the understanding is not there.”

Canadians are, “…stuck in a narrative that is way, way back in the past which has nothing to do with the current situation.”

The government has to deal with resource inequality, he said, as it relates to everything – education, housing, social services, child welfare. Giving First Nations jurisdiction but no resources to do it, “is just wrong,” Rae said.

The other challenge for both parties is deciding what to do with existing treaties, whether to breathe new life into them, or rely on litigation or negotiation. These challenges require real political leadership, he said, and as long as political leaders rely on the lengthy litigation process, injustice will rule and demonstrations will likely increase.

In response to a question about the missing and murdered Aboriginal women, Rae said a national inquiry would be useful.

“There has to be some attention paid to why it’s taking so long to get answers and how policing can be improved,” he said. “It’s a problem with a national scope. It’s not simply confined to one police force…it’s a more systemic problem and a systemic problem requires a systemic answer….there are some challenging issues that need to be investigated and need to be discussed. That’s something a national inquiry can do.”

- 3379 views