Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

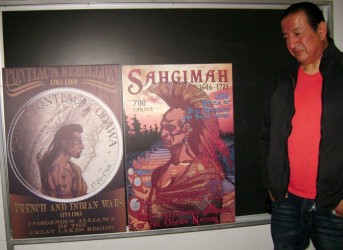

Artist Philip Cote wants to educate the country about Indigenous heroes, one school at a time. He’s created a series of 11 posters spanning 350 years as part of his Master’s thesis at Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto.

The series starts with Sahgimah, Odawa Chief, described as “the leader most feared by the Iroquois”, and ends with internationally-renowned singer and activist Buffy Sainte-Marie.

“These people are all defenders of the land, defenders of the people, defenders of the culture,” said Cote. At a recent exhibition at Toronto’s Fort York, he told the 50 people assembled for his artist talk that his work is a counter-narrative to the colonial version of history that is being taught in the schools.

Each of the 24”x36” posters is a history lesson and a well-executed and attractive work of art.

For Chief Sahgimah (c. 1646-1721), Cote created a piece similar to an epic movie poster. Sahgimah led a war party of 4,000 warriors travelling in 700 canoes against the Haudenosaunee. The Mohawks, said Cote, were encroaching on the hunting and trapping territory of the Three Fires Confederacy, a situation created by the British insatiable need of beaver pelts. One of two sites for this battle against 2,000 Mohawks took place at Blue Mountain, the now popular Ontario ski resort. The other site is Skull Mound by Lake Erie.

“A lot of Anishnawbe people know who Sahgimah is,” said Cote, “but I don’t think the rest of the world knows just how important he was for the Anishnawbe people in defending the territory. How come we don’t hear about it?”

This is exactly what motivates Cote’s work with his thesis and his posters. Indigenous youth need to know about these heroes so they can situate themselves in Canada’s history and the world.

“We are still without recognition as a nation,” he said, “and Canada and the U.S. had an opportunity to change that and they didn’t. So we are still in limbo as a nation of people that are without representation on the world stage.”

Who has heard of Jean Baptiste Cope, the Mi’kmaq leader who signed the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty with the British? He signed the treaty with his clan symbol, the beaver, Cote said. Around the time the treaty was signed, the Mi’kmaq had a bounty on their heads.

“Their scalps were worth money,” he said and so he designed something that resembles a ‘Wanted’ poster. No images exist of the leader and Cote drew him based on drawings of other Mi’gmaq people at that time. Cope signed the Peace Treaty not so much to acknowledge the British sovereignty and territory, said Cote, but more to protect his people.

The British awarded Cope the designation of Major, a frequent occurrence at that time according to Cote. “It was a military action, the British coming here. This wasn’t just about looking for new land for settlement. They were looking for new territory. But at no time did our people ever become Generals. It was always Major.”

Cote’s posters feature leaders from the east coast to the west, “who rose up to defend their territories” as colonial territories expanded. “The Europeans had a very different idea about what progress meant,” said Cote. “Progress meant they were going to make a lot of money and they were going to do it through the fur trade. The fur trade expanded those colonies right into the interior of North America.”

Maquinna, or Possessor of Pebbles, was chief of the Mowachaht, Nuu-chah-nulth people of Nootka Sound who were affected by the expanding colonies. The Spanish arrived in Maquinna’s territory, said Cote, and “claimed this whole territory without even asking any of the Native people.”

Cote, who’s a member of Ontario’s Moose Deer Point First Nation, wants to see the posters going into all the educational institutions and Friendship Centres and “wherever there are Aboriginal youth programs so our people can begin to create a dialogue about their place here.” That’s just for starters, he said.

In Toronto, he wants to lead a guerilla-style postering action to plaster the city and he’s already got several volunteers lined up to help, “to offset and balance that idea that we are not out there in the public domain. It’s important that an Indigenous person be responsible for bringing those images out from an Indigenous perspective.”

Tecumseh, Pontiac, Black Hawk, Joseph Brant and Russell Means are other First Nations heroes featured on Cote’s posters. The posters will be available for sale in August and Cote is developing a web site for the distribution.

- 2679 views