Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

In response to the growing crisis of dwindling Indigenous languages, members of an art group with a social action agenda have come up with an interesting—though intensified—way to create new Indigenous speakers.

Members of the Onaman Collective—Erin Konsmo, Christi Belcourt, and Isaac Murdoch—have launched “Language Immersion House” projects across Canada. The original three were held in Ontario, while a fourth, the Nehiyawewin Cree Language House, is coming up April 8 to April 10 in Edmonton.

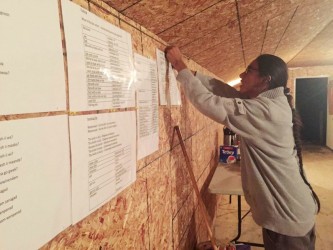

Caption: Preston Pine is at home-at work in an Anishinaabe Wiigwaam (Anishinaabe Language Immersion House) in Serpent River, Ont.

Photo Credit: Erin Konsmo

“We’re still doing active recruitment right now… We’re looking for First Nations, Métis and Inuit, and we’re prioritizing young people. But they need to have a commitment to learning the language, so the language stays over the long term,” said Konsmo.

“We’re creating that community of people who want to support each other in learning… and we’re looking to create more fluent speakers and language teachers for the future,” she said.

The previous three Languages Houses were held in Ontario, and called the Anishinaabemowin Wiigwaams. Anishinaabe is the language of some First Nations there.

Despite a change in the Indigenous language being taught in the house, the formula for all four is the same, involving one very key ingredient for success.

“The phrase we’ve been using is ‘Anishinaabemowin Eta.’ It means ‘Anishinaabe only.’ If someone speaks English, we send them to a corner, or send them to a picture of the Queen, and say ‘Go speak English to the Queen,’” said Konsmo, adding that while it can be frustrating, participants are not even allowed to venture outside to a store for food.

“It’s difficult… It’s super difficult to not just break down and say ‘I don’t understand.’ If you have a question, you have to ask it (in the language). And if you can’t, you just have to deal with not being able to ask it,” she said.

Other features of the Immersion House formula include an opening-day ceremony, done mostly in English with bits of the Indigenous language in it, introductions to one another, and an overview of house rules and the schedule for the following days.

Within the house there are as many as seven learners, between the ages of 16 and 30, with as many as 10 language speakers, of any age, but most often First Nations Elders because Elders are the population most likely to be fluent.

The Elders are treated respectfully, and operate on rotating shifts so they don’t have to be present 24-hours a day. Sometimes the commitment is as simple as stopping in for tea and bannock—which of course is prepared, talked about, and consumed, all in the Indigenous language.

“From 9 a.m. to 8 at night, we’re doing lessons, games… We’ve been doing crafts at the Anishinaabemowin Language House. We did birch bark earrings, so we’re learning the words for thread, needle, to sew. That type of variety can be difficult, too, since people have different learning abilities,” said Konsmo.

It was Christi Belcourt of the Onamen Collective who held the first Language House in her home in Ontario last year. Belcourt and a younger friend, Taryn Pelletier, 19, had just been talking about wanting to learn Anishinaabe, then very quickly decided upon the Immersion House strategy. Both thought it would be the most effective way to learn, and the project snowballed from there.

“It’s really doable… It’s not complicated to set up. You pick a date, get a house, and you start organizing. You have to have offerings and a little bit of money to help out the Elders who come there… and tobacco, of course. And you gotta’ feed people,” she said.

“It’s a really a grassroots way of trying to increase fluency in a very intensive atmosphere… You’re learning faster than you could taking one-hour courses here and one-hour courses there,” said Belcourt.

Belcourt and her co-organizers even get to participate in the houses as they hold them; so they, too, are learning as the project moves along. But operating on a volunteer-basis can be difficult, and with no government funding as a source of support, it’s really their convictions and their passions about the language that keeps them motivated. Even the house they hold the Immersion House in is borrowed, said Belcourt.

“The language is essential to our identity. It’s essential to our nations. The language is central to who we are as Indigenous people,” she said.

“As people of the land, as people of the water, as people of the stars… We have to understand all of the spiritual realm that’s around us. And we can’t do that to the fullest extent that our ancestors did, unless we understand our languages,” said Belcourt.

- 3742 views