Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

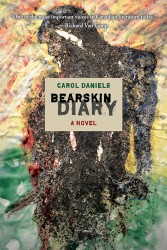

A novel recently published by well-known Canadian journalist Carol Daniels brings to light issues surrounding missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Bearskin Diary is the story of a young girl who was taken from her family by the Canadian government, and placed in foster care during the 1960’s. To Daniels, the “60’s Scoop” was one of the last great efforts at the assimilation of Aboriginal Canadians, but the effect of that historic act left a devastating mark.

“There’s lot of things people aren’t going to like… there’s sexuality, and some really ugly behavior,” said Daniels. “Not necessarily from the main character, though she does her fair share. But it’s a really frank look at racism, and a brutal look at what First Nations have to go through,” she said.

Daniels, who often writes children’s literature and short stories, acknowledges the book is much darker than many of her other works. But she also acknowledges because the issues raised in the book are real issues, faced by real people, being honest and sometimes even profane is important.

The plight of the main character, which includes broken family ties, experiences with abuse, and the erasure of her identity—all after-effects of the 60’s Scoop—is talked about candidly in the book, and according to Daniels, for good reason.

“Sometimes I think ‘What if anyone had done that to me?’ I was a single Aboriginal woman with children, and if they came and said ‘You’re not married, you’re not capable of taking care of these kids,’ I think ‘Oh my God, that would have destroyed me’,” said Daniels.

The novel has actually been in the works for nearly eight years, but raising three children, and working as a full-time news anchor kept her from finishing earlier. Her children being her biggest concern in life, gave her extra empathy for her characters’ griefs, and outside research added fuel to her fire.

“The young lady in the novel is placed with a Ukrainian family, so I had to do research on the customs you would have in your family… I didn’t know Ukrainian families were put in concentration camps in Canada during World War I. That made for a good story because the grandmother could identify with her granddaughter (the main character) who was Cree,” she said.

Even Daniels’ own artwork is featured on the cover. The piece, in real life, is a 5-ft by 4-ft painting modelled after a story told to her by an Aboriginal Elder. The Elder vividly recalls running to hide as a child, every time he heard the Indian Agent’s vehicle driving up along the road near his home.

The man’s experiences took place before the 1960’s, but because the government was already taking Aboriginal children from their families to be placed in Indian residential schools, that fear was already commonplace.

“It’s made with dirt, and acrylic, and all sorts of materials,” said Daniels of her painting. “And if you look closely, there are skulls in the body of the Indian Agent. I’m happy they went with my image, because for the story of the scoop up, it was the same thing…” she said of the similarities between stolen children in the residential school system, and the stolen children of the 1960’s.

Daniels’ novel has actually been placed on the winter syllabus at the First Nation’s University in Regina. And she is eager to educate the public about the larger picture behind her novel.

As for her favorite part of the story, she is most proud of the fact that the main character, Andy, at one point is finally able to come to terms with her life experiences, and challenge some of the identity issues she has picked up along the way.

“She goes to a powwow,” said Daniels. “And she’s terrified because she doesn’t know what to expect. But before you get to that part you realize she’s got a lot of ideas that are not hers that have come to her because of her brown skin...† And she’s touched by her experience, in a good way that changes her life,” she said.

This is where Daniels really hopes she’ll be able to reach people. While the novel is only one year of the main character’s life, it’s the year that is most significant. Daniels hope that as the main character unravels some of her trauma, readers, too, will find a new understanding of themselves, or people they might know.

“If there are people out there who don’t know anything about our culture, it might serve as a starting point to learn about us,” she said.

“And if you happen to be an adult who doesn’t know anything about the culture because of the 60’s scoop, I’m hoping they’ll say ‘Gee, I need to learn, and undo some of the things that were said to me…’ And stop believing somehow they aren’t worthy’,” she said.

- 2737 views