Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

The existence of Minamata disease (methyl mercury poisoning), with symptoms that include tremors, clumsiness, loss of balance, blurred vision, speech impairment and slowed mental response, is not acknowledged in this country.

Health Canada consistently refuses to accept that it has occurred, even in Canada’s worst-hit communities of Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows) and Wabaseemoong (Whitedog) where mercury released from a Dryden chlor alkali plant from 1962 to 1975 poisoned an entire river system and devastated the health and economy of those who lived downstream.

Residents and supporters of the two Northwestern Ontario First Nations communities recently took to the streets of Toronto to demand recognition of the fact that they’re still suffering into the second and third generations, 40 years after fishing was banned in the English and Wabigoon rivers.

“It really hurts when Canadian doctors say we’re pretending, or it’s not really happening,” Grassy Narrows Chief Simon Fobister told an emotional meeting in Kenora last month, where mothers struggled to hold back tears as they described their children’s deteriorating health.

And now fishing is being allowed again, and consumption of those fish, within certain guidelines (avoid the larger fish and some lakes), has been declared safe. It shouldn’t be happening again, say some.

Health Canada determined in 1995 that mercury levels in the First Nations residents were below a safety level of six parts per million. But a study from Dr. Masazumi Harada suggests Canada needs to take off the blindfold and face this health problem.

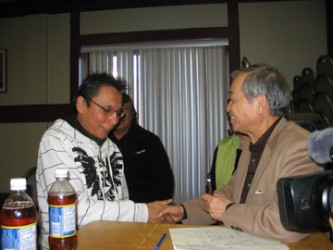

The Japanese mercury poisoning expert diagnosed Minamata disease at Grassy Narrows and Whitedog when he first visited the two reserves in 1975. He returned last month for the fifth and last time (he is 75 and not in good health) where he released a 2005 study that has just been translated.

It found that residents with mild symptoms in 1975 showed almost typical symptoms of Minamata disease by 2002, significantly impairing their ability to function. This despite lower levels of mercury in their bodies.

Harada, who was called a “travelling troubadour” in 1975 by then Conservative Natural Resources Minister Leo Bernier, had already spent 15 years treating victims in Minamata, Japan where an estimated 2,000 people died from exposure to high levels of mercury.

The chemical company that polluted Minamata Bay denied responsibility, as did Japan’s government.

Thousands of Japanese patients were excluded from compensation and treatment and had to fight for both through the courts. The most recent legal action ended last month with 2,000 Japanese patients accepting a settlement that will be extended to 30,000 others.

For Canada to acknowledge that Minamata disease exists in Ontario could imply liability, legal processes, punitive damages and costly remediation, all of which are powerful incentives for government to look the other way.

That’s the thesis of a study by biologist Michael Gilbertson who examined Health Canada data from 1986 to 1992 and found statistically elevated hospitalization for male cerebral palsy in several Great Lakes communities, including Sarnia, Cornwall and Thunder Bay, all areas where there were chlor alkali plants like the one in Dryden (all now closed).

Gilbertson concluded there is reason to suspect previously undetected outbreaks of congenital Minamata.

The symptoms of Minamata disease are varied and change through the patient’s lifecycle. Congenital Minamata cases are the saddest ones. Exposure in the womb leads to cerebral palsy and developmental delays. Research in Japan, Iraq and elsewhere indicates that male fetuses are more susceptible.

In an interview, Gilbertson emphasized that more research needs to be done.

“We need a series of epidemiological studies to find out, are there incidences of Minamata disease that are occurring, and what we should be really responding to in terms of cleanup?”

His paper, titled Index of Congenital Minamata Disease in Canadian Areas of Concern in the Great Lakes: An Eco-Social Epidemiological Approach, was published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Health in October 2009.

A spokesperson for the International Joint Commission (IJC), a body whose role it is, in part, to implement the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between Canada and the United States, said the commission has not reviewed Gilbertson’s study, but pointed to its 2004 biennial report that included a section on mercury. It makes no reference to the Health Canada data, but does recommend epidemiological studies. No such studies have been carried out.

Gilbertson, who worked for the IJC for 16 years, argues that the bilateral agency’s mandate of restoring water quality has been abandoned because of an ideological shift towards deregulation and eliminating barriers to development.

In this climate, research that suggests stricter regulation of risk to human health is dismissed as “junk science,” he writes.

- 4805 views