Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

Folk singer, filmmaker inspired a nation

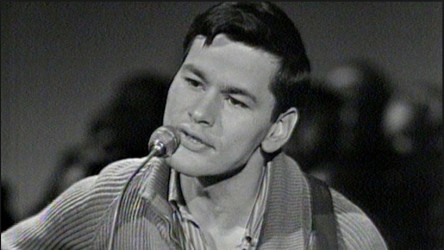

Early black and white CBC television footage depicts a young, strikingly handsome Willie Dunn singing in a strong, clear voice as he expertly picks his guitar in accompaniment.

A railroad tune penned by his Scottish father, and a haunting ballad of love lost are well-performed, but carry none of the gravity his future compositions would hold.

Influenced by the flourishing folk music scene of the late 1950s, his songs increasingly focused on Aboriginal oppression. With few role models other than Buffy Sainte-Marie and Floyd Red Crow Westerman, and amidst overshadowing Viet Nam war protests, his songs gained attention for their impassioned poetic punches.

The musician and filmmaker’s 1968 The Ballad of Crowfoot, containing lyrics like “we’re all unhappy pawns in the government’s game and it’s always the Indian who’s to blame” became his signature song. It was made all the more poignant in 1971 when Dunn juxtaposed it with National Archives of Canada photos and footage of traditional Aboriginal people for the National Film Board. The production decried the inhuman and unjust colonial treatment of his people down the years, as well as encouraging them to take charge of their destiny and become politically active. It was the first music video made in Canada.

“My father’s (words) were poignant for people who were dealing with the issues … and he was the only one saying these things,” Lawrence Dunn, Willie’s son, told CBC radio’s All in a Day. “After he would perform, people would come up to him and hug him or give him gifts. I remember lots of travelling to concerts and festivals. I was a kid running around but I remember seeing him up on stage and I was really proud of him, proud of his musical ability and proud of how much people seemed to look up to his music and poetry.”

When Willie played Son of The Sun, a deeply spiritual song about the sacredness of being Aboriginal, eagles flew in to circle the outdoor stages at many of his concerts.

“At first it was kind of mind-blowing, but it happened so often it became kind of normal,” Lawrence said. “’Oh, here’s the eagle again’, we would say.”

Following The Ballad of Crowfoot, Willie stepped further into filmmaking. His other NFB credits include directing the short These Are My People and The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company. He also made an environmental documentary The Eagle Project, and another on First Nations languages The Voice of the Land.

His music was used for the films Incident at Restigouche, about a 1981 police raid on the Listuguj Mi’kmaq First Nation, and Okanada, about the 1990 standoff in Oka, Quebec between Aboriginal protesters and police.

Dunn’s mother was Mi’kmaq, giving him the ancestry he was so proud of. Though he was born west of her east coast homeland in Montreal, the seventh of eight children, the eclectic city would offer him musical inspiration.

When he returned home from serving in the army at 23, the husband of one of his sisters gave him a guitar, and Dunn wandered the city listening to blues musicians as he taught himself to play. A decade later, he found himself onstage at Café Lina in New York, a national historical site of folk music where rising stars of the genre played.

Dunn’s widow, Liz Moore, who accompanied Lawrence in the CBC radio interview, mentioned her husband was the kind of guy who liked to try something new.

“He was a go-getter. He was passionate in life,” she said.

He liked experimenting with different genres (including country and traditional Aboriginal) and even set the words of William Shakespeare and T.S. Eliot to drumming and chanting.

His full-length albums include Willie Dunn, The Pacific, Metallic and Son of the Sun.

Lawrence noted his father’s friends, including Phil Fontaine, former head of the Assembly of First Nations, and Métis politician Harry Daniels, who pushed each other to be more active and vocal.

Willie let his name stand as a one-time political candidate for the NDP, defeating Mohamed Bassuny to win the party’s federal nomination for Ottawa-Vanier in the 1993 election.

“He was a big supporter of the NDP and all they stood for. He stood for socialism, Lawrence noted.

Edmonton’s Terry Lusty, a Métis journalist who dabbles in music, recalls jamming with Willie in a north-end theatre in Winnipeg in the 1970s.

“He was a personable guy … my friend. He’d do anything for a colleague. Even with his role in the film world as an award-winning director, that never seemed to change him. He was humble and mingled with anybody and everybody.

“He liked his freedom. You wouldn’t see him working nine to five. As an artist, he liked to accept or reject projects as the spirit moved him.”

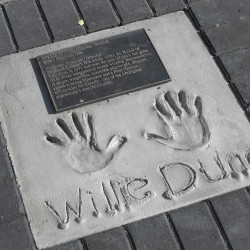

Inducted into the Aboriginal Walk of Honour during Edmonton’s 2005 Dreamspeakers Film Festival, Willie’s handprints are in a cement plaque along with other trailblazers in the film industry. He is also credited with having brought new understanding to Aboriginal culture in being awarded a lifetime achievement prize at the Canadian Aboriginal Music Awards.

He was the consummate Aboriginal ambassador. “In Germany my father was a rock star,” wrote his daughter Pamela Kalloosit Dunn on a CBC Web site.

In Canada, a Mohawk chief gave him the name Roha’tiio, meaning “his voice is beautiful”.

According to Lawrence, the lyrics in his father’s early songs perfectly encapsulate the issues Aboriginal people still face today.

“He was sick during the Idle No More movement. He wasn’t tuned in to what was happening, but he liked hearing about it.”

Willie, who was born on Aug. 14 in 1942, passed away on Aug. 5 at the age of 71 at his home in Ottawa.

- 4305 views