Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

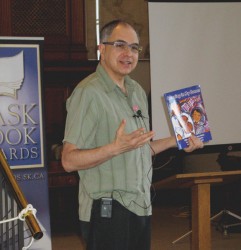

The 2009 Saskatchewan Book Award winners shared their works at a full house during a May 12 lunch hour reading at the Legislative Library in Regina. Aboriginal authors at the event were Métis writers Jo-Ann Episkenew and Wilfred Burton.

Episkenew won the ‘Scholarly Writing Award’ for her PhD thesis “Taking Back Our Spirits: Indigenous Literature, Public Policy, and Healing.” Meanwhile Burton, who was the big winner in 2009 with “Dancing in my Bones,” – co-written with Anne Patton, illustrated by Sherry Farrell Racette, and published by the Gabriel Dumont Institute – captured the ‘Award for Publishing’, the ‘First Peoples’ Publishing Award’, and the ‘First Peoples’ Writing Award’.

Being in the magnificent library, a room with huge windows and so many old books provided beautiful ambiance for the reading, Burton said.

“Jackie had warned us that there would be a come-and-go group,” Burton said referring to the organizer Jackie Lay. “Because the reading was held over lunch hour. But nobody was up and down; they all stayed for the whole thing.”

Burton, who has a series of children’s books in the works, read one to the crowd.

“Everyone else had to choose little pieces from their book to read. My book is a picture book; I can get through it in about 7 minutes, so I got to read the whole thing which was nice. An older lady commented to me after, ‘I just love being read to - that’s not just for children,’ so it went very well.”

Through previous readings Burton said he has learned that children’s books can reach an adult audience. Even though it’s written for children it has messages for everybody and everyone can connect to it in some way.

“Many people grew up neighbours to Métis people but they actually don’t know anything about them or their history. I find that quite sad,” Burton said, adding that children’s books can be wonderful tools in bringing Aboriginal issues to a wider audience in a non-confrontational way.

“I use children’s literature to make quite political points with teachers as well. I’ve always known I was Métis, but when I was growing up I never saw myself portrayed in any books until high school when we got into ‘the history of’, and then it wasn’t always the most positive portrayal either,” he said.

Episkenew, who had just returned from an academic conference in Germany, would agree with Burton’s assessment.

“The myth of the new Canadian nation-state valorizes the settlers but sometimes misrepresents and more often excludes Indigenous peoples,” she stated.

Episkenew said while overseas, she asked her doctoral supervisor what she should read from her book at the reading.

“He said, read the beginning, help people understand why you wrote the book, why it was necessary, and why it was necessary to do your PhD in Germany,” she recounted.

“When I started, there was no-one over here who had done their PhD in Native literature. There wasn’t anybody who knew about this stuff,” Episkenew said.

Indigenous literature, she added, “acknowledges and validates Indigenous peoples’ experiences by filling in the gaps and correcting falsehoods in the master narrative.”

At the reading, Episkenew took her supervisor’s advice and read out the passage from her book.

“In my second year as an undergraduate student I had an epiphany. I realized that all knowledge worth knowing – or, more specifically, knowledge that my university considered worth teaching – was created by the Greeks, appropriated by the Romans, disseminated throughout western Europe, and through colonialism eventually made its way to the rest of the people of the world who apparently were sitting on their thumbs waiting for enlightenment,” she said, referring to this situation as an assault.

“As a Métis woman, I knew that Indigenous communities had created a body of knowledge that enabled our ancestors to survive for millennia before the Johnny-come-lately new nation-state of Canada established itself on top of Indigenous peoples’ lands,” she said.

Episkenew spoke at the reading of Indian policy: what it had done to Indigenous peoples, and what people need to know to make good policy.

She related Canada’s historic ills with regard to Indian policy to present-day issues for the audience.

“For example, if the First Nations University of Canada closed down, people assume kids can just go to mainstream universities and learn the same things. Who’s going to teach them? Where are they going to get the teachers? The mainstream educational system is horribly flawed, Eurocentric, and oozing with white privilege. It doesn’t recognize that other people in the world had knowledge,” she said.

Episkenew said there were about 50 people who attended the reading and were open to hearing about the Aboriginal issues, that she addressed.

“When I spoke, I saw quite a few heads nodding in the right places, so that was nice,” she said.

Other award-winning authors at the event were Trevor Herriot author of ‘Grass, Sky, and Song’ and Margaret Hyrniuk, author of ‘Legacy of Stone: Saskatchewan’s Stone Buildings’.

- 3300 views