Article Origin

Volume

Issue

Year

Ceremonies and information sharing sessions are becoming key parts of the Royal Alberta Museum returning the Manitou Stone to the First Nations.

Anna Faulds has been organizing meetings concerning the repatriation of the stone.

“There are still many people to hear from about their experiences with the Manitou Stone, and those that heard about it from their Elders,” said Faulds, who is Dene Suline from Cold Lake First Nations. “All of this must be taken into consideration before movement can take place.”

The most recent event took place on March 22 at the RAM and marked a significant step in the repatriation of the stone, as it combined traditional ceremony with intercultural and interfaith dialogue.

“I know the stone is here, but we really are its stewards at the moment. We’re not going to be in the way of what should happen to this stone. We recognize that it certainly is not ours,” said Chris Robinson, executive director of the RAM. The museum does not charge admission to people who wish to visit with the stone for ceremonial purposes.

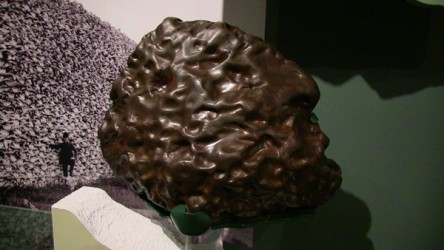

Also known as the “Peace Rock,” the Manitou Stone fell to earth as a meteorite several centuries ago in the Iron Creek/Battle River area. It was taken to the Pakan Mission near Smoky Lake by Methodist minister Rev. George McDougall in the 1860s then moved to Lac Ste. Anne. In 1886, the stone headed east to Victoria University in Cobourg, Ont., followed by Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum. In the early ‘70s, the Alberta government requested the stone be loaned to the Royal Alberta Museum, where it has resided since 1972, first as part of the Museum’s geological display area, then as part of the RAM’s Aboriginal gallery in 1997.

A prophecy that taking the stone away would lead to tragic consequences for First Nations may have a connection between the removal of the stone and war between the Cree and Blackfoot Nations, the near-extinction of the buffalo, and the devastating smallpox outbreak.

Faulds has been following a vision which began in June 2012. While in Jasper doing a ceremony in the mountains, she discovered the story of the Manitou Stone in a book. Faulds learned more about the stone’s history and has been trying to bring about forgiveness and reconciliation between First Nations and the United Church of Canada. The Methodist Church is one of four churches that combined to form the United Church.

“I think that the Manitou Stone is one of the most important artifacts that’s in this museum… because it represents in a profound way the relationship between people in this land,” said Jim Graves, a member of the United Church who spoke at the March 22 session. “If the stone is free and able to have its power, it guarantees for us prosperity, peace amongst the people, and health to the community.”

Representatives from Blue Quills First Nation College asked Victoria College to transfer the stone to their institution in 1999. However, as there was no consensus among First Nations as to who would house the stone, title to the Manitou Stone was transferred to the RAM. RAM embarked on a consultation process with over 30 First Nations in Alberta and Saskatchewan between 2002 and 2004. Many did not support Blue Quills’ request to get the stone because it would be housed on one specific Nation.

Others felt it should go back to its original location, with an appropriate facility and security. Yet others were fine with it staying at the museum, but in a separate area where ceremonies could take place in private.

Vincent Steinhauer, president of Blue Quills, believes the Nations should employ traditional means to reach a decision on where the stone should ultimately go. “I think we should get into ceremony in a ceremonial lodge and don’t leave there until we come to a consensus - the way we used to do things, instead of the divide-and-conquer colonialism that is running amok right now.”

Blue Quills First Nation College is starting construction of a ceremonial lodge this spring and considers it an ideal place to house the stone.

In the meantime, Faulds plans on organizing more meetings, “so we can hear from anyone who has something to share. This needs to happen very soon, so we don’t lose momentum. I am very focused on the task at hand, so I will continue to work towards completing it.”

No formal request has been made to the government by any First Nation for the stone.

- 4703 views